21 Feb Doing the Math on “Success” in the Theatre

At a grocery store just after New Years, two young men working at the register were talking about the minimum wage increase, which had recently taken effect. They were quite excited to be getting $11/hour ( $12/hour if you work Sundays!).

It was heartbreaking to listen to on many levels – the least of which was my desire to tell them it should be more. It struck me that these two young men were making more money at my local grocer than many theaters are willing to pay for a master’s degree worth of knowledge and experience. It reminded me of a conversation I had a few months earlier with some young people in college.

“Whatever it is, it can’t be financial loss.”

This from one of my students as we chatted over our sewing projects, discussing the possibilities for work in the summer.

“I didn’t mind the long hours, but once I did the math, I didn’t like the low pay” another student chimed in, discussing a summer stock job from the previous year. Their hourly rate had dropped below $3 an hour once they completed the assigned 60 hour work week.

It’s a problem many face. How do you get the experience needed to succeed in our field, when you still need need to make money to pay for college or repay student loans? Then, how do you find a job to sustain yourself in life?

“Fresh out of college I took one of these summer stock jobs, halfway across the country knowing full well the pay would be awful, but knew it was what I needed to do to get experience. I was desperate, and honestly it was the most discouraging thing. While I met some amazing people and gained a lot of experience, it nearly broke me emotionally. […] I feel defeated. I guess I just want to know from those who have way more experience than me, how in the world you all possibly do it? I feel like I’ve waded through thousands of jobs who either pay nothing or next to nothing and now I’m just left over-educated for a job I can’t get.”

– Haley B.

When I graduated from college with a degree in dance 20 years ago and got my start in the costume business, I scraped together jobs to make my way. In general, I made $10 an hour for my work, usually assisting a dance designer in fittings as well as stitching. I made $1000 in a flat fee working for a prominent dance school when they had their dance concerts. On top of this, I maintained 2 part time jobs to fill in the blanks.

I also sacrificed a lot of things in my quest to “make it” in the business. I clearly remember a time I was backstage, acting as Designer, Builder, AND Wardrobe attendant. It was tech weekend and we were on a meal break. I had so much to do and I was determined to work through dinner. The Stage Manager and TD, bless them, would not have it. They forced me to eat a meal. Never before had I needed someone so much to tell me I needed to eat.

Think really hard about that story for a moment. First, it shouldn’t sound familiar, working through a break instead of eating, but I bet it does. Second, I was in the position I was in because I was not provided adequate budget to hire other people to help me. I was a one-woman show and I never even questioned it.

This pattern of being asked to work endless hours for very little pay continued. I was at the very least able to maintain an additional part-time job to support my costume habit. But more and more we see advertisements for theater jobs that require 10 hour days 6 days a week. Asking people to regularly work that many hours is unsustainable, regardless of whether or not the person themselves can afford to take the job (usually due to family or spousal support). Summer Theatre is especially guilty of these unrealistic expectations.

When we train our students to sacrifice their well-being in order to “make it” in this business, it’s wrong. What are we saying about our business and the value of the college education we push on young people in the industry when we fail to provide trained professionals enough income to make rent?

“I’m significantly older. […] I have made a relatively similar amount each year for the past 20 years though it buys far less than it did particularly since health insurance is a much greater cost now. And I work juggling crazy hours at 3 to 4 jobs all the time. […] Not feeling like I’ve ever “ made it” or will ever retire. But everyone loves my work. I was recently let go from a long standing gig after a big push for better pay ( basically what the feds put into place 3 years ago which many non-profits ignore or say doesn’t apply to them.) […] But how do we create real change ? How do we up the value of our work so the payment offer isn’t in the poverty zone to start?”

– Julie Englebrecht

More and more, we are seeing jobs posted with wages that have stagnated for 20 years. A recent one asked for a First Hand with 5 years experience and expert level skills to put in a 45 hour work week for $500 a week…nearly the same hourly wage as the young men I overheard at Shop Rite make for their service. A valuable service, to be sure, but nobody was asking them for a college degree and 5 years of experience in the field to earn their meager wage.

What of the expenses that we all need to cover? A generous budget might include such things as rent, utilities, mobile phone (which we all know is a necessity not a luxury), internet, groceries, health insurance, and student loan repayment. Assuming the expenses of a healthy 22 year old out of college, using national averages their expenses might look like this:

- Rent (shared 2 bedroom): $600 (1)

- Utilities (half share): $40 (2)

- Transportation: $300

- Mobile phone (least expensive plan): $15 (3)

- Internet (half shared): $25 (4)

- Groceries: $250 (5)

- Health Insurance : $106 (6)

- Transportation costs (gas and auto insurance): $325 (7)

- Student loans (based on a $48k loan): $267 (8)

Total monthly expenses: $1,928

One of the ways I made low pay work in my youth was having a consistent part-time job at the same time as I worked to gain experience in the business. This strategy is becoming increasingly impossible as more and more theaters are listing these positions as full time and often require 10-14 hour days 6 day a week. Even if we eliminate housing and utilities, a young worker still has $638 a month in base expenses. A $100 a week stipend leaves more than a $500 deficit and $250 a week nearly a $200 deficit after taxes. Where is the rest supposed to come from?

Wages are not the only problem. Stress, lack of sleep, and isolation are major negative factors affecting our industry. Combining low wages with an impossible schedule and no time to visit friends and family has cost the mental and physical health of our “theater family” dearly. If we care so much for our community, why are we not meeting its needs? Why have these same theaters who have used our loyalty and love of the art not returned that loyalty to us? Despite this culture of family, many workers report feeling uncomfortable with complaining about their hours or asking for a raise.

“I made the most money I’ve ever made in 2019 but my quality of life has been horrible! Lots of work (yay) but not any time for friends or family or sleep or to cook or work out… so the balance is sort of out of wack!”

– Sarah Smith

The process of bringing theatres’ wages up to a livable standard is a bit of a conundrum. By allowing pay to stagnate, companies have created an impossible task to bring wages back up to par. Most businesses allow for a 2% cost of living increase for employees every year. Many theaters have not done this. Additionally, recent minimum wage increases will put theatre’s lowest earners very close in hourly pay to their supervisors. It’s a hefty price to raise all wages.

It’s hard to feel much sympathy however when an abundance of theatres large and small are solving that conundrum by misusing internship and apprenticeship programs in an attempt to circumvent minimum wage and overtime laws. Laws, by the way, that have been in place since the 1930s.

We are told over and over that we will kill theaters if we ask for a fair wage. As if it is the cost of our labor that is to blame for failing to plan for inflation and sustainable growth. As if creeping administrative bloat is a byproduct of our demands. Asking for fair pay is not killing the theatre. The theatre is killing itself by failing to adapt to a changing economic climate and by driving away the very people who make the theatre they are trying to sell. More and more, people are considering giving up or have already given up a career in theater because they simply cannot sustain themselves and their families.

“Both my husband and I work in educational theater design and love teaching. We are also on staff at the same university. We both have master’s degrees from a top school. We have two kids, a small house (under 1000 square feet) and a small dog. We both are able to put into a retirement and have ok heathcare ins[urance]. We still live paycheck to paycheck. We have no savings and no cushion in our checking. […] I am seriously considering leaving theater altogether but can’t because the idea of not having health care anymore is just unfathomable. […] I love what I do but can’t afford to do it anymore, and on the other side of the coin, I can’t afford to leave.”

– Cathleen Perry.

How can we change this culture? First, I believe those of us who hold upper level positions need to lead by example. For 8 months a year I work as an Adjunct and Costume Shop Staff member at a university. One of the best examples I can set is leaving work at 6pm every day. I’m not saying there is never a time for extra hours – tech weeks mean a 60 hour work week for me – but my students should see it as just that, an exception.

If I see a fitting schedule that does not allow for lunch for my designer, I ask the stage manager to reschedule a fitting. The culture of respect in the costume shop needs to extend to the other areas as well.

Finally, we can ask those in the position of hiring to carefully consider the skills, hours, and expectations for the wages offered. Start that conversation before posting the job ad. Present a realistic budget to those who hold the purse strings. When presented with a low wage, offer reduced hours so that the person taking the job can work another job. Compare the Costume Shop wages with those in other areas and make an effort to equate skill level with pay.

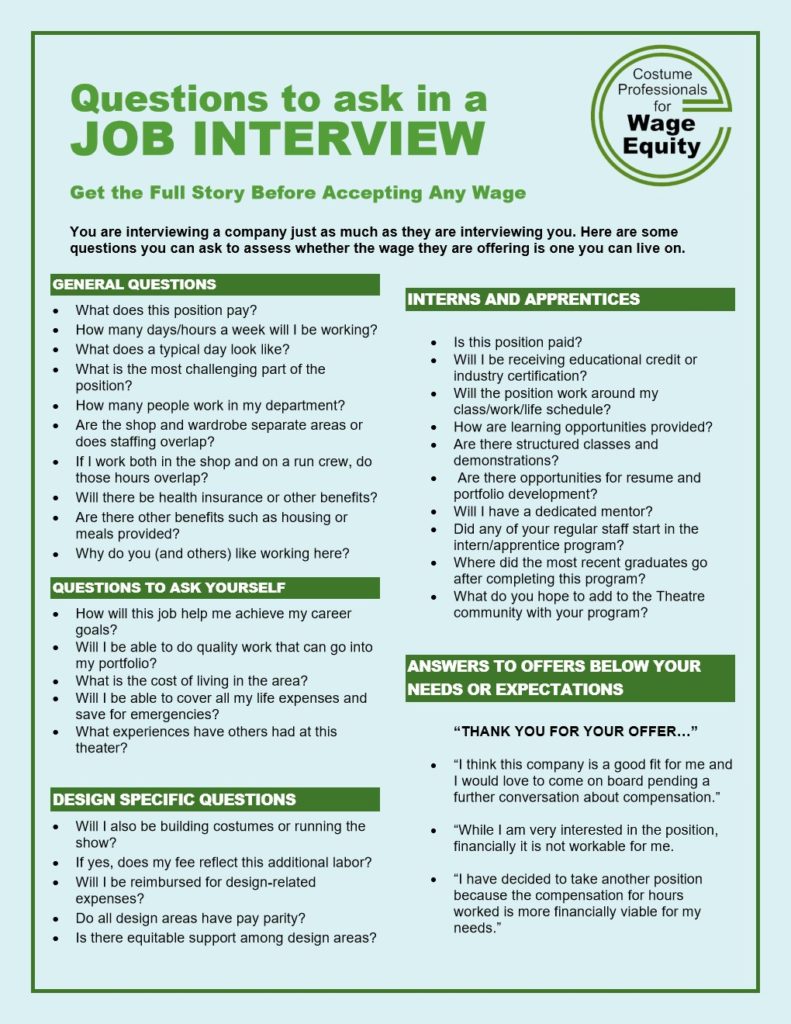

Job seekers can help change the industry by asking hard questions in interviews and being vocal about their reasons for turning down a position that asks too much for too little. Not everyone feels they are in a position to turn down work. Those that do end up taking these jobs can still recognize and use their privilege to advocate and negotiate for better wages and conditions. Workers in other departments can become allies by sharing information and encouraging management to seek parity within the organization.

“I’m 33 […] and confronted with the fact that I could make as much working a ‘normal’ job with much less stress. Kids are possibly on the horizon for me, and thankfully my partner has a well paying job. Otherwise, that could never be an option for me. My priorities are shifting, and I’m examining whether a career in theatre is “worth it” anymore in my life.”

– Amanda

The industry can only improve by respecting its workers. Raising wages reduces stress, because it means our workers don’t have to worry about paying their bills. Reducing hours to 40 a week means that people have time to spend with their families and cook healthy meals. Employees with fulfilled personal lives and lower stress do higher quality work in less time. Experienced designers and technicians who no longer feel the need to cram in as many gigs as possible to make ends meet will take less lower-tier jobs, leaving those positions open for early-career professionals to cut their teeth on. A healthy industry needs healthy workers. Making a living in the theatre should mean that workers are able to make a life for themselves.

“I think that’s the definition of a living wage. Not just barely getting by with the bills but able to save for retirement and a house and support kids if you choose to have them. We shouldn’t have to rely on a spouse to have those things as is often expected in this industry.”

– Mariah B.